Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has transformed European LNG supply dynamics, pushing countries to purchase record volumes of the supercooled fuel as they look to cut their dependency on Russian gas while maintaining energy security. However, with the war triggering the construction of new LNG import infrastructure across the continent, there is a risk that regasification capacities will far outweigh future import requirements, leaving assets redundant and unused.

Just weeks after the invasion, EU leaders announced an intention to phase out the bloc’s dependency on Russian fossil fuels. Russian gas deliveries to the EU plummeted as member states faced rouble payment issues and doubled down on efforts to find alternative supplies. In 2021, Russia supplied EU countries with 40% of their fossil gas, with Germany, Italy and the Netherlands ranked as the largest importers. That had dropped to around 17% by August 2022.

Despite the progress made in curtailing the flow of Russian pipeline gas, EU imports of Russian LNG increased by 12% in 2022 compared to 2021, with France, Spain, Belgium and the Netherlands sourcing the most. This is part of a wider trend that saw Europe’s LNG imports surpass those coming to the continent via pipelines for the first time in 2022.

Plans for new LNG regasification terminals have been announced accordingly. More than ten European markets have started constructing new regasification capacity or expanding existing facilities since the war began, according to recent research from the International Gas Union.

Germany became a new LNG importer last year, while Italy’s fourth regasification terminal – the Piombino facility, which features a floating storage and regasification unit – received its first LNG cargo in early July.

However, this scramble to build new infrastructure doesn’t match forecasted gas demand, which peaked in 2010 and is poised to fall as a result of high prices, energy efficiency, plans to cut emissions and demand reduction, among other reasons. EU countries collectively reduced their fossil gas consumption by 19% between August 2022 and January 2023. This amounted to 41.5 billion cubic metres (bcm).

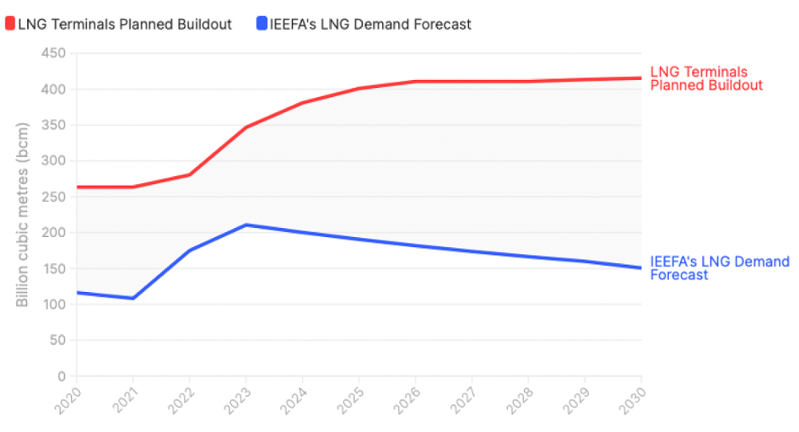

IEEFA research found that while new LNG terminals could boost Europe’s import capacity by one-third by the end of 2024, energy transition targets could cause much of the new capacity to be unused. Indeed, the continent is on track to have 400 bcm of operational LNG import capacity by 2030, but demand for LNG is unlikely to exceed 190 bcm.

Europe’s planned terminals buildout demand forecast 2020-2030

Source: GIE, IEEFA

With the EU planning to slash fossil gas demand by at least one-third by 2030, decision-makers must avoid tipping the scale from reliability to redundancy when it comes to LNG infrastructure buildout.

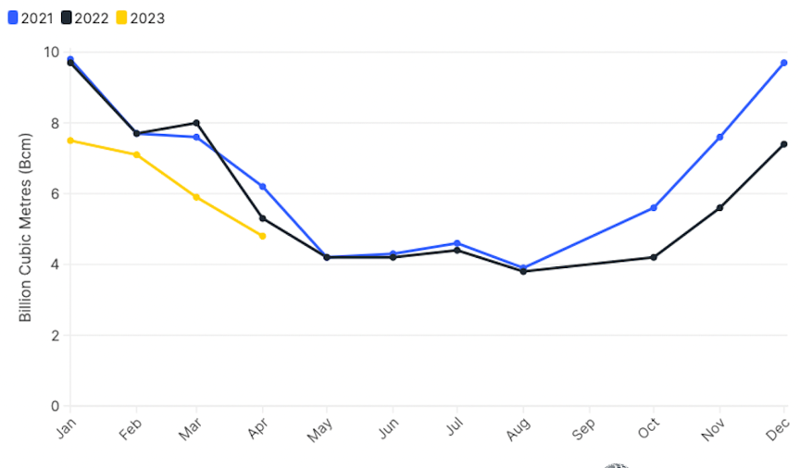

Italy is a case in point. The country’s gas consumption in June 2023 dropped to 3.7 bcm, representing the lowest value in 2023 and a 13% decline on June 2022. Meanwhile, renewables deployment is skyrocketing: Italy added nearly 2.5 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity in the first half of 2023, a 120% increase on the same period of 2022, according to electricity grid operator Terna.

Italy's Monthly Gas Demand (2021-2023)

Source: Eurostat, IEEFA

Considering the REPowerEU policies being implemented to accelerate the energy transition, IEEFA estimates that Italy’s gas demand and LNG imports will continue decreasing through 2030, resulting in a less than 50% utilisation rate of its LNG terminals that will be operational at that time.

Bullish outlooks for European LNG demand are often based on planned increases in regasification capacity. However, import capacity is not an accurate indicator of LNG demand. Gas transmission system operators (TSO) are often incentivised to overbuild infrastructure to increase shareholder returns, even if the assets are not used or required.

In Spain, under the premise of achieving security and diversification of supply, the country’s monopoly TSO Enagás has created a significant oversupply of underutilised gas infrastructure to secure revenues, leaving Spanish consumers with some of the highest gas prices in Europe.

LNG becomes a global commodity

With LNG prices becoming more volatile and impacted by factors such as extreme weather, economic crises and geopolitics, the fuel is now being traded as a global commodity. The fall in Russian pipeline gas deliveries to Europe since the invasion of Ukraine left European countries jostling to source replacement energy supplies, causing LNG prices in the continent to soar. As LNG spot prices reached record highs last year, some lower income economies in Asia were effectively priced out of the market, leading them to increase their dependence on coal.

Amid significant differences in LNG prices between regions, some sellers have diverted cargoes contracted under long-term agreements to buyers that are willing to pay more, with the gains more than offsetting penalties for breaching contracts. Thus, LNG is becoming an expensive and unreliable fuel source.

As new LNG import infrastructure comes online in the EU, member states must coordinate with each other to handle additional volumes efficiently while avoiding the unnecessary buildout and maintenance of redundant gas infrastructure. Decisions to expand Europe’s portfolio of LNG terminals should be made following a comprehensive assessment of available infrastructure while taking into account energy transition targets.

With Europe’s energy crisis laying bare the pitfalls of depending on imported fossil fuels, markets across the continent have increased the rollout of technologies that displace gas and LNG, such as heat pumps, solar power plants, battery storage systems, demand response and energy efficiency upgrades. Faced with the energy trilemma of finding a balance between security, affordability and sustainability, governments should make smart decisions about the buildout of LNG infrastructure to avoid an oversupply of import terminals come the end of the decade.