It is nearly two months that European Union’s seaborne crude imports from Russia have come to a halt (with the exception of Bulgaria), while we are days away from the EU ban on Russian oil product imports becoming effective on 5 February. The widespread sanction scheme also limits the use of EU vessels, insurance and other services for Russian oil exports to third parties. G-7 countries and further partners are implementing similar sets of sanctions.

Does this mean that Russian oil flows are coming to a halt? The answer is generally “no”, but let’s start with crude oil first, where we have already nearly two months in the full sanctions regime. While seaborne exports of Russian crude oil temporarily dipped by 500kbd or 15% in December according to Vortexa data, they are staging a strong comeback in January, and are set to end the month higher than in November and 24 out of the previous 32 months.

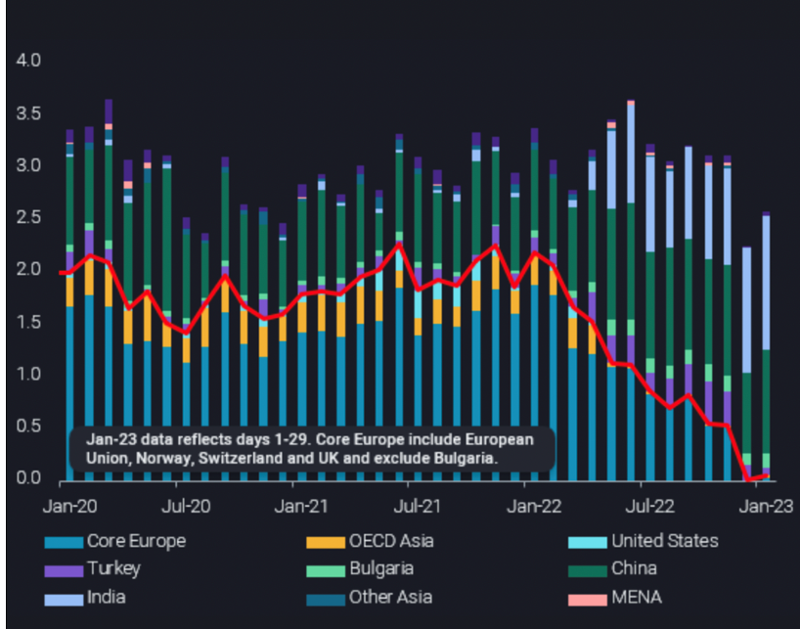

Imports of Russia crude oil by selected markets (mbd)

Source: Vortexa

India has become the biggest buyer of seaborne Russian crude oil, taking between 1.2-1.3mbd over the last two months. China temporarily hesitated in December, but inflows are back to about 1.1mbd in January. Only some 200kbd are going to any other countries, led by Turkey. For comparison, in 2021, less than 30% of seaborne Russian crude oil moved to China, India and Turkey, with the majority going to EU countries, while a combined 13% or 400kbd landed in Japan, South Korea and the United States.

The switch in destinations is coming along with substantial changes in the logistical chain. First of all, most shipments are now handled by a mix of players based in Russia, India, China and the Middle East – in the case of the latter three often new market entrants. Before Western majors and European companies were mostly in charge.

Secondly, the trips are now of course much longer and partly also more protracted. This means that much more vessel capacity is required. But it also serves as a warning signal that not every vessel that leaves a Russian port has necessarily already a willing buyer. In other words, high export flows in the early days of full sanctions are not necessarily sustainable. Apart from missing buyers a lack of vessels may still emerge in a later point in time.

Finally, to mitigate pressure on vessel supply and partly also to disguise the origin of the crude, ship-to-ship transfers are becoming much more frequent. More than 20% of Russian crude exports via Europe are now transferred from smaller feeder vessels to VLCCs, mostly offshore Ceuta in the Western Mediterranean or in the Kalamata area off Greece.

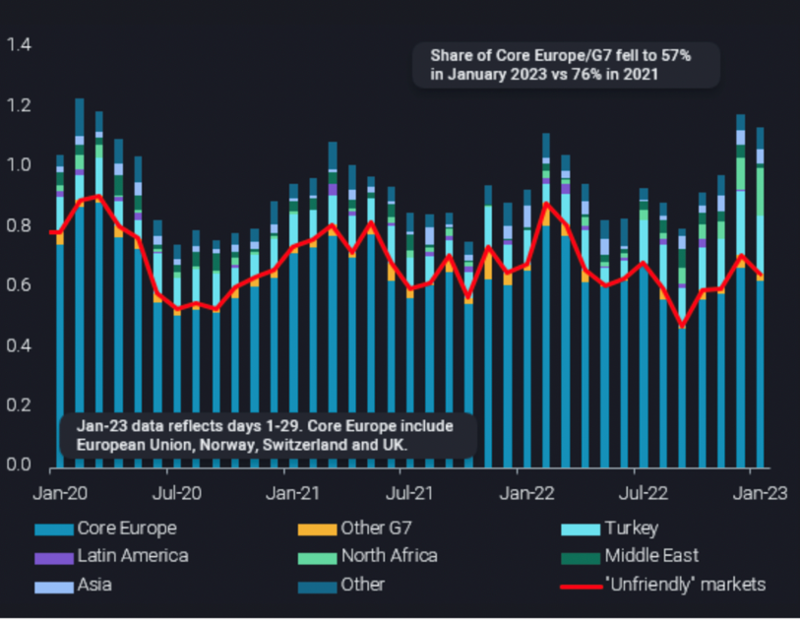

Many market commentators are concerned that the reshuffling of Russian products, especially diesel, may not work as easily as for crude. However, similarly to dirty tankers used for crude oil shipments, new market entrants have also bought up a sizeable fleet of clean tanker. And on the clean side it would be even easier to transition from the usual smaller MR vessels to bigger LR1 or LR2 vessels. North African countries have already started to increase imports of Russian diesel, but some 600kbd still need to find a new home. This compares however favourable to imports of 1.5mbd into Africa and the Middle East from external sources, of which Russia serves less than 200kbd so far. These markets have so far been serviced largely by Asia, European and Middle Eastern players, which could in exchange supply the open European needs.

Imports of Russia diesel by selected markets (mbd)

Source: Vortexa

This means that the additional vessel needs may be limited, and European import demand is likely to be well-supplied, as illustrated already in the case of crude oil.

Does this mean that sanctions are ineffective and just raising logistical costs? It is surely true that European buyers have to pay a few dollars more per barrel to procure non-Russian crude and products, but in most cases this will be in the singe-digit range. In comparison, the discount Russia has to accept to find buyers for its crude and products are roughly around $30 per barrel and in tendency rising. This is boosting the Russian urge for income. The fact that diesel trades at around $140/b makes it very likely that Russia will maximise its efforts to keep supplies flowing. Even with a discount of $40/b it would earn about twice as much as on the average crude barrel. This should then help to ensure sufficient global diesel supplies and may ultimately contribute to lower diesel prices at the pump.

This market analysis is provided courtesy of energy analytics firm Vortexa and written by their chief economist David Wech.