Trends in global oil demand continue to shift. Consumption is set to keep growing in emerging markets, but an uneven pace in the transition to less carbon intense sources of energy clouds when plateauing or declining oil demand takes hold. The adoption of EVs, stronger regulatory frameworks, technological innovation, and geopolitical issues also play significant roles in influencing both demand and supply dynamics. The future of oil demand will depend on how countries balance energy security, sustainability goals, and economic growth.

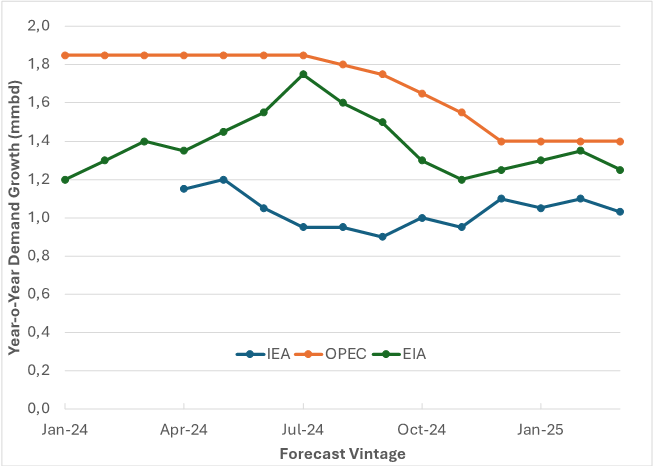

Through the course of 2024, there were large differences in short-term demand growth estimates across forecasters. Major revisions in global demand were driven mainly by China, which registered combined growth of 0.16 mmb/d (million barrels per day) compared to 0.57 mmb/d projected at the start of the year. Globally, demand grew for gasoline and jet, while contracting for diesel and fuel oil.

Many demand outlooks are converging to a consensus view that demand grew 0.83 mmb/d in 2024 and in 2025 will accelerate to 1.0 to 1.1 mmb/d (see Figure 1), with OPEC remaining a bullish outlier at 1.4 mmb/d. Product mix is expected to remain similar to 2024, with LPG and naphtha leading the gains with the start-up of new petrochemical plants in China. Growth across the product barrel could provide some reprieve for refining margins, especially if announced refinery closures in Europe and the US (approximately 0.8 to 0.9 mmb/d) materialize.

Evolution of Global Oil Demand Forecasts

Source: IEF, IEA OMR, EIA STEO, OPEC MOMR

US oil & gas executives are more vocal and less apologetic about their business with an emphasis on the need for continuous investment. Oil executives value consistency, stability and predictability in policy—but many are not seeing these today.

Given the adaptation of US oil companies to capital discipline and stable returns to investors, it is difficult to imagine a dramatic increase in drilling activity. US crude production will continue to grow, but likely at a more moderate 0.2-0.4 mmb/d, rather than a return to +1.0 mmb/d growth of President Trump’s first term. Growth from NGLs (driven by growing natural gas production) and other liquids will augment these gains.

The US has been a key driver of non-OPEC supply growth for about a decade, with growing contributions from Canada, Brazil, Argentina, and Guyana. This trend continues as essentially all the growth in non-OPEC supply will continue to come from these five countries.

It appears that 2025 will be the year that OPEC+ will begin to return excess capacity. The solidarity of the group, going on five years, has been stronger than most market observers expected back in 2020. We expect the group to follow a phased and strategic approach to minimize the risk of market disruptions. Consistent with their 3 March 2025 announcement we expect OPEC+ to restore production incrementally, with some offsets for prior over-production by some members. However, OPEC+ will continue to monitor the market for changes in global demand and non-OPEC supply growth and then adapt as necessary.

Not all OPEC+ members have the same ability to ramp up production so the group might allocate increases based on each country’s production capacity, which could favor members with higher spare capacity (e.g., Saudi Arabia, UAE). They likely maintain voluntary constraints for members struggling with investment constraints or geopolitical instability (e.g., Nigeria, Venezuela).

If demand weakens or prices drop too quickly, OPEC+ would retain the option to maintain strong cooperation within the group by pausing production increases or even reintroducing temporary cuts.

Trade sanctions on Iran and Venezuela also have the potential to significantly shape how OPEC+ unwinds its excess oil production capacity. If production in Iran and Venezuela were constrained, other OPEC+ members (e.g., Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the UAE) could have more room to increase output without oversaturating the market. However, if sanctions on Iran and Venezuela are lifted or eased, they could quickly ramp up exports and potentially over supply the market. Thus OPEC+ might delay full production increases in case Iranian or Venezuelan crude unexpectedly returns to the market. This holds the dual advantage of reducing the risk of the market being over-supplied and potentially results in a more bullish price environment.

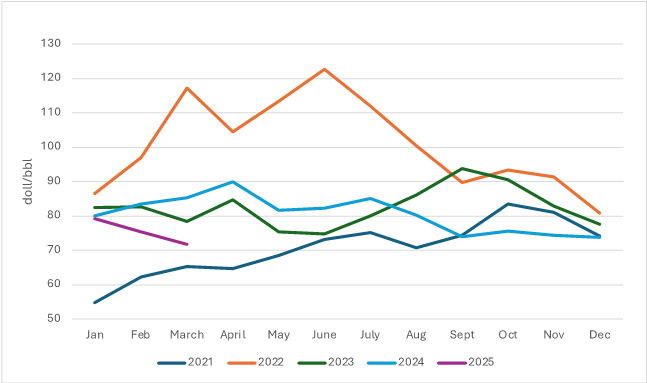

Except for the world emerging from COVID in early-2021, oil prices are at a three-year low (see Figure 2). Compared to the beginning of last year, Brent is almost $15/bbl lower, but demand growth is expected to be slightly better and supply growth somewhat muted from then. The mercurial tariff policy of President Trump has exacerbated international trade risks. The risk to the global economy is retaliatory (and escalating) trade measures, which could dampen demand growth. The changing geopolitics of trade is spilling over to oil market fundamentals.

Brent oil price by month

Source: EIA DOE

A key question is at what level do oil prices settle such that the US consumer (recall President Trump’s campaign promise of cheap energy) and US oil & gas industry are equally satisfied. We see Brent oil prices in the mid-$70s as a reasonable range for market expectations, although economic uncertainties may result in slight downside risk to this level.