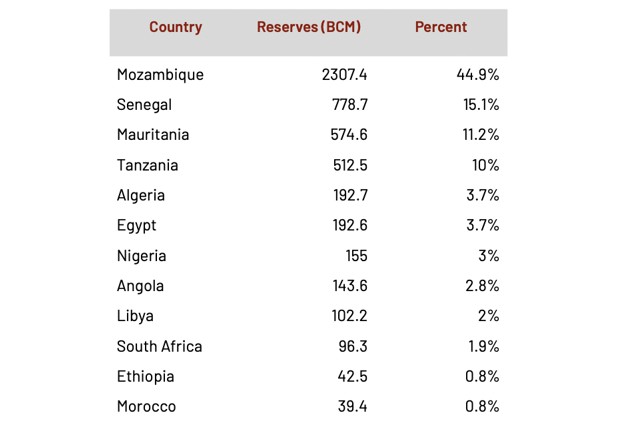

A seismic shift is on the horizon for gas extraction in Africa, with many of the new pre-production fields proposed in countries that historically have not exploited fossil fuels, a trend that would run counter to the global scientific consensus calling for a halt to the construction of new fossil fuel infrastructure. Global Energy Monitor’s (GEM) Global Oil and Gas Extraction Tracker (GOGET) includes data on 421 extraction projects, with 79 fields in the pre-production stages. While historically Nigeria, Egypt, Libya, and Algeria have had the most proven gas reserves and production, data in GOGET show that 84 percent of new reserves in pre-production are located in recent entrants to Africa’s gas market—Mozambique, Senegal, Tanzania, Mauritania, South Africa, Ethiopia, and Morocco.

Pre-production reserves in Africa by country

Source: GEM Global Oil and Gas Extraction Tracker

These new reserves total more than 5137.5 billion cubic meters (bcm), with potential emissions equaling about 11.9 billion tons of CO2, with production from many of these fields facing opposition due to the potential impacts to local ecosystems and communities. These countries are expected to drive gas development volumes in the near term, with ‘Mozambique, Mauritania, Tanzania, South Africa, and Ethiopia accounting for more than half of Africa’s gas production by 2038.

If industry plans for this wave of new gas field extraction projects are allowed to proceed, Africa’s gas production would increase by a third by 2030. An estimated US$329 billion greenfield investment is required for the development of both gas extraction and export infrastructure.

Yet most of these gas field developments are destined for export, doing little to address low electrification rates across the continent. Many of the in-development gas extraction fields are explicitly tied to new or existing LNG export terminals. Much of the gas from new projects is destined to leave Africa, possibly for Europe and Asia. Investment in LNG export terminals continues to take priority even as African countries are faced with unmet domestic demand and limited electricity access, while also exposing Africa’s energy mix to the volatility of gas markets.

African investment in the development of extraction infrastructure in previously undeveloped areas will likely lead to serious impacts on locals’ health and the environment, while exacerbating climate change and reducing Africa’s ability to invest in its own energy transition and the electrification of its communities.

So while Algeria, Nigeria, Libya, and Egypt will continue to be big players in the production of gas in Africa, new market entrants will claim a growing market share. But growing domestic demand to meet Africa’s own energy needs and the shrinking window of opportunity to exploit EU and Asian markets threaten the long term success and durability of new market entrants’ plans.