Armed clashes broke out in the middle of last month as rising tensions between the two generals leading Sudan’s rival military units spilled over. On the one side, there is general Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Sudan’s de-facto leader who heads the army, and on the other, general Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, who heads the RSF.

The two factions had been sharing power in the country since the military coup in late 2021. That coup dissolved a civilian-led transitional government that had been installed following the ouster of long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019 to help move the country towards full-fledged civilian rule. The military and civilian leaders signed a political framework agreement in December of last year, which was supposed to lay the grounds for the formation of that civilian government over a two-year period.

But tensions between the army and the paramilitary group had been on the rise in recent months, largely over how and when the RSF would be integrated into the army ꟷ a key condition for the transition to civilian rule ꟷ and more importantly, what that would mean for the influence that the two generals wield.

The fighting quickly spread to a number of locations in the capital city, Khartoum, including the presidential palace and international airport. Today, despite repeated announcements of ceasefires, the clashes continue and remain most concentrated in the capital, although there have also been reports of battles in other cities including Omdurman and Bahri nearby, Darfur in the west, and Port Sudan on the Red Sea.

So far, officials and sources on the ground say that the fighting has yet to materially impact the oil sector – not only in Sudan, but also in South Sudan which remains intrinsically linked with its neighbour to the north, despite seceding from it back in 2011.

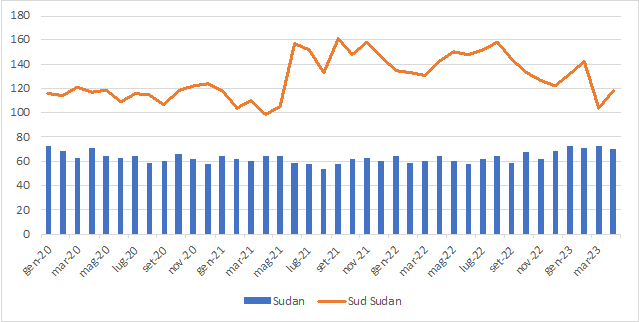

Both countries are members of the Opec+ alliance, with their respective production concentrated along the border that they share with one another. Sudan pumps a modest 70,000 b/d, and South Sudan around 170,000 b/d. But, while Sudan has access to the Red Sea to export its crude, South Sudan is landlocked, which has forced it to rely on Sudan’s Bashayer terminal, around 25km south of Port Sudan, to export its own oil.

Like Sudan, South Sudan sends the bulk of its crude production north by pipeline to Sudan’s Red Sea coast for export, with a portion of it going to Sudan’s only operational refinery, a 100,000 b/d capacity plant around 70km north of the capital, to supplement what volumes Sudan, itself, sends to the refinery.

Combined crude exports from both Sudan and South Sudan averaged 80,000 b/d in the first four months of this year, according to Vortexa data, down from 116,000 b/d last year. Three tankers have left the Bashayer terminal, all loaded with crude, since the start of the fighting.

And its downstream activities at the Khartoum refinery, too, have also been largely unaffected, with the facility continuing to produce enough to meet up to 60pc of domestic fuel requirements. The remainder is typically sourced through imports to the Bashayer terminal.

Sudan and South Sudan crude output ('000 b/d)

Source: Argus Media, South Sudan Ministry of Petroleum

But with little sign of a let up in the fighting, fears are growing that the critical oil sector - the lifeblood of both countries’ economies - could soon be dragged into the conflict.

Already the city of Port Sudan and the vicinity around the Khartoum refinery have witnessed clashes. Port Sudan temporarily fell under the control of the RSF in the early days of the conflict, before being retaken by the army the following day. And just last week, the RSF also said it had taken control of a complex housing both the Khartoum refinery and a key power plant, only for the government to reclaim control just two days later.

Sudan’s energy minister Mohamed Abdallah Mahmud says the refinery is now safe and operating at full capacity. But, officials say a lack of safe transport routes to deliver the fuel to filling stations is already leading to fuel shortages, and in turn, a more than doubling of the price of fuel at the pump. The instability is also hampering the import of petroleum products – like gasoline and diesel – into the country, which is further exacerbating the shortages in Sudan and South Sudan.

South Sudan’s oil minister Puot Kang Chol has said his country will consider importing fuel through Djibouti or Kenya by truck if the situation does not improve. But this would likely limit the volumes of product it can bring in because of the difficulty and expense of sourcing the required number of trucks.

And worse yet, South Sudan has warned also that crude exports ꟷ particularly from the south ꟷ could be seriously affected, not only if the pipeline is caught up directly in the fighting and damaged, but also if the fighting hampers its ability to import and source critical materials needed to maintain production at its oil fields.

Relative to global production and consumption, the volumes this conflict could impact are small. But for Sudan and its neighbour to the south, the repercussions of losing these flows will be considerable.