The US operation that took place in Venezuela in the early hours of January 3 is nothing short of historical. While it indeed represents the end of the Nicolás Maduro-regime, it is also the beginning of a new period that, as of now, we know very little. Ten days after such events, the current environment is one of shock and uncertainty, one in which questions abound and answers are scarce and meagre.

For one, President Trump announced that same day that the US “would run” Venezuela, and that then Vice President Delcy Rodriguez, a long-time Maduro associate, would be sworn in as Maduro’s successor. In the next couple days, the same regime sans Maduro and with a large armada of US Navy fleet in the Caribbean vicinity sworn Delcy Rodriguez as acting President. The next few days in Venezuela have been marked by repression in the streets of Venezuela as well as the harassment of armed groups in motorcycles known as colectivos. Later in the week, Secretary of State Marco Rubio detailed the US rather than running Venezuela was exerting “control and leverage over what those interim authorities” do and will be able to do. A few days later, Trump outlined a plan to sell up to 50 million barrels of Venezuelan-produced oil under sanctions that the US would sell at “market value”, and then that money would be used to “benefit the people of Venezuela and the United States”, the specifics of such plan are yet to be made public.

From day one, Venezuelan crude oil has been front and center on almost every speech and interview from either Trump and any of his cabinet members. On the one hand, this is little surprising given that Venezuela holds the largest oil reserves in the world with about 17% of the total. On the other hand, Venezuela’s production was not quite relevant as a share of global supply, accounting for less than 1% at around 0.9 million barrels per day (mb/d). This fact highlights the importance that holding the largest reserves of crude oil by no means translate in the ability of swiftly bringing enormous production of oil to the world’s market. Moreover, Venezuela crude oil distinguished itself for being known as extra-heavy oil, which means it is denser, thicker and sludger compared to other types of crude. Because of this, its extraction requires a higher level of energy-use, specific infrastructure, technical expertise and blend it with oil distillates. More energy for oil extraction means more carbon emissions, which makes Venezuela’s oil one of the most carbon-intensive in the world along with the Canadian Oil sands and some Iranian blends. On top of that, this crude is also sour, or with high content of sulphur, which requires special set-ups for its refining and processing.

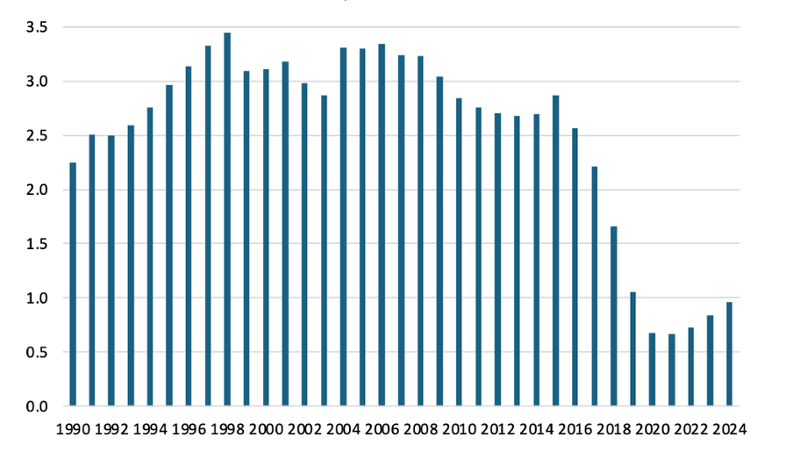

Venezuela’s oil production peaked in 1998 at around 3.5 mb/d, driven by state-owned company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) and joint-ventures with international oil companies. In 2007, then President Hugo Chávez forced the increases of the participation of PDVSA in the oil industry and the companies that refused to reach an agreement, got their assets expropriated. This followed years of mismanagement, lack of investment, corruption and, later sanctions, led to the collapse of the Venezuelan oil industry, dropping output by 80% to less than 0.7 mb/d in 2020, and then slowly recovering to current levels.

Venezuela’s crude oil production (1990-2024, mil. b/d)

Source: Energy Institute, 2025

Trump’s statements on whether and how oil production can ramp-up in Venezuela. However, any significant raise on oil production in Venezuela would require copious amounts of investment, on the order of tens of billions of US dollars. Moreover, reverting an almost two-decade long trend is not impossible but it would require apart from the financing, infrastructure development and rehauling and plenty of time. This would only be possible with some minimal preconditions of governance and stability, as well as a sound legal and regulatory framework regulations and law and clear incentives for companies to invest in Venezuela, something easier to say than to do, and a minimal set of pre-conditions that today are clearly not there. Evidence of this were some of the comments of executives from oil executives at the White House on January 9th. Exxon Mobil’s CEO was perhaps the clearest, saying out-loud in the Presidential House what perhaps some of his peers shared, Venezuela is currently “uninvestible”.

Looking ahead, the global demand outlook looks rather uncertain, but across many scenarios by the likes of Rystad, BP and the International Energy Agency, with very limited growth and plateauing sometime in the 2030’s. For instance, demand for transportation is a key driver of oil products, however global electrification trends are growing robustly and last year 1 out of every 5 car sales worldwide was electric.

Moreover, on the supply side, the current oil market is relatively oversupplied and any potential additional Venezuelan crude volumes would face stiff competition from other producers. Just in the Latin-American neighborhood, Brazil and Argentina have significantly increased their oil production in the last five years, while Guayana has emerged from zero to almost surpass Venezuela’s current production according to preliminary data from 2025. In sum, the Maduro dictatorship is over but whatever the political landscape turns into is right now far from clear and that would be a crucial variable of the impact it may or may not have for Venezuelan oil production.