In 2022, the European Union experienced the most severe energy crisis in decades. When the EU backed Ukraine against Russia’s invasion, the reduced gas flows towards the EU pushed prices upwards. Therefore, an unexpected surge in electricity, heating and transport fuel prices hit households and businesses. As price spikes spread all over the economy, these effects created an inflationary trend that threatened vulnerable income groups and brought into sharp focus their distributional impacts. The EU promptly created a legislative framework to tackle the crisis. EU Members States (Member States) shortly followed, collectively introducing 657-billion-euros-worth of national temporary measures to reduce the burden of energy prices. Although such measures were similar, their effects were different due to Member States’ social, economic and political contexts. In a joint study, the Basque Centre of Climate Change (BC3) and the Institute of European Environmental Policy (IEEP) found evidence of the social impacts of the energy crisis across EU Members States.

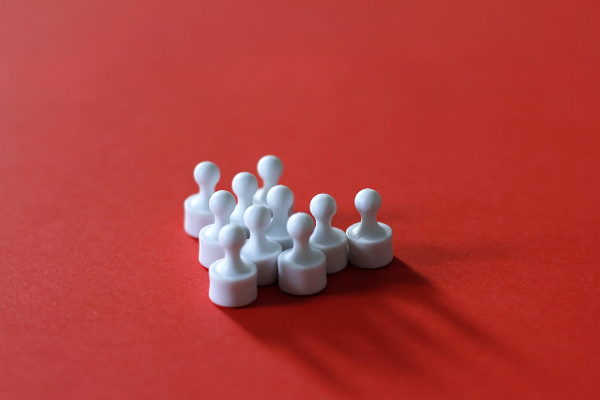

Price impacts (%) of the main energy commodities by Member States in 2022

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

First, price changes were heterogenous across commodities and Member States. It could be that some Member States dealt with electricity price shocks better than others due to a more resilient energy mix or a better control on downstream prices hitting consumers. Moreover, while some Western Member States were hit more than Central and Eastern Member States by electricity price shocks, the effects of fossil fuel prices on the transport sector were quite homogeneous across EU. Thus, the larger the share that energy has of a households’ expenditure the more significant the price shock on that household.

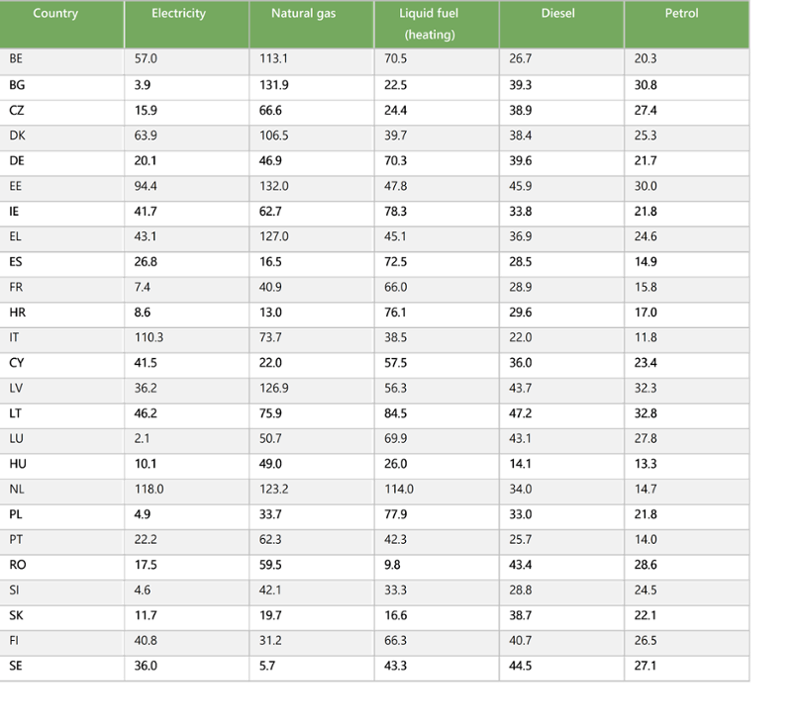

Welfare impact (% of total expenditure) in the EU due to energy prices

Source : García-Muros et al (2023)

The welfare impact by income decile at EU level confirms that the energy crisis follows a regressive distributional pattern. Namely, the poorest households spend more on energy than the richest ones. Therefore, the progressive effect given by an increase in fuel prices – consumed proportionally more by the richest households – did not counterbalance the regressivity of electricity price shocks.

While some Member States showed a regressive distributional impact, others were characterised by progressivity. This result can be justified by two reasons. One is how each Member State dealt with energy prices and their own energy sources, depending for instance on whether electricity was produced by fossil-fuels or renewables. Another reason is the consumption structure: Member States have different income levels and therefore different energy expenditures.

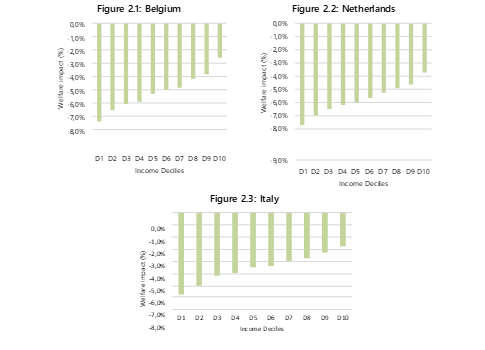

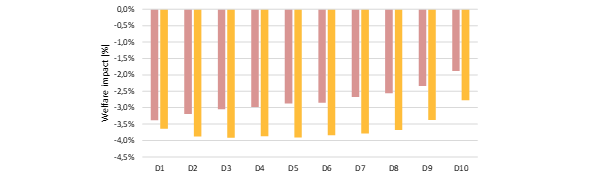

Welfare impacts on Western countries affected more for electricity prices

For instance, Western EU Member States show regressivity, as several of them suffered from particularly high electricity prices which affect low-income deciles most.

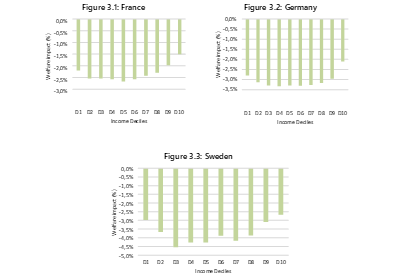

Welfare impacts on Western countries affected more for fuel prices

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

On the contrary, Western Member States severely hit by high fuel prices experienced a different pattern. It turns out, they suffered less welfare losses than MS hit by high electricity prices, but it was the middle-income deciles who were affected the most, due to a larger income share dedicated to transport.

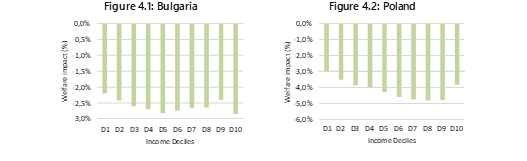

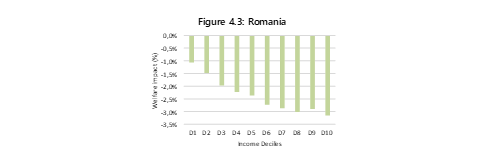

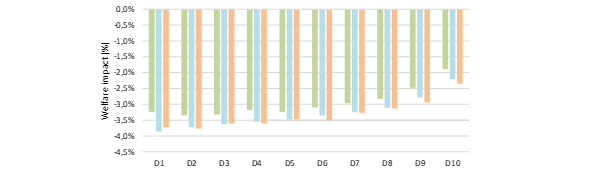

Welfare impacts on Eastern and Central countries

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

Looking at Central and Eastern countries, these Member States were shown to be more vulnerable to fuel prices for heating and transport purposes. In this case, however, fuel prices affected middle- and high-income deciles most.

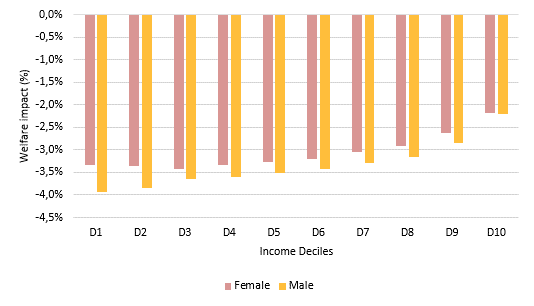

Welfare impact (% of total expenditure) according to reference person by gender

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

In line with prior evidence on gender inequalities in energy and transport, female heads of households are hit less, as they are affected by fuel price shocks much less than male heads of households. This offsets the electricity and heating price shocks, which are more harmful for female heads of households than males. As women tend to spend a larger share of their income on housing energy bills and caring activities, this leads to them suffering from high energy prices at home more than men. On the opposite, women are less likely to have a car and more likely to use public transports and walk. The impact varies according to the MS analysed but where electricity prices were not adequately controlled, female heads of households were affected more than their male counterparts.

Welfare impact (% of total expenditure) according to living area

![]()

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

Two major results can be drawn here. First, rural areas were more vulnerable to energy price shocks than urban areas. Second, the effect on urban households were mostly regressive, while in rural areas middle-income households were hit most. Also, due to a larger share of income devoted to private transport, middle income deciles were affected most in rural areas as they are the ones who tend to devote most of their income to private transport, while the lowest income deciles might not own a car at all.

Likewise, IEEP and BC3 checked impacts according to different age categories: young, adults and the elderly (age groups were aggregated as follows: below 35 years, "young"; between 35 and 65, "adult"; and above 65, "elderly").

Welfare impact (% of total expenditure) according to age

![]()

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

Regardless of income, the elderly are hit by price shocks more than younger households, and the same stands with respect to middle-aged adults in most income deciles.

What if Member States implemented generalised VAT reduction on electricity?

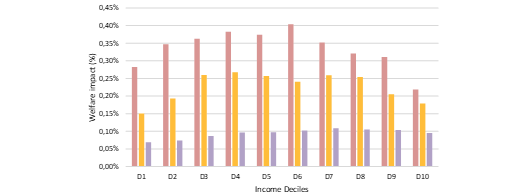

Welfare impact (% of total expenditure) in Policy Scenario 1

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

Using Belgium (pink), Portugal (yellow) and Netherlands (violet) as examples, by controlling electricity prices through a decrease in VAT, Member States would have supported low-income deciles the most. However, high-income groups would benefit as well, therefore Member States would have provided transfers also to the richest households (next figure).

What if Member States reduced excise duties to everybody?

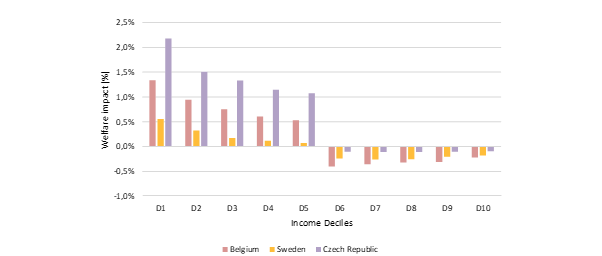

Welfare impact (% of total expenditure) in Policy Scenario 2

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

According to the results, middle- and high-income deciles in Belgium (pink), Sweden (yellow) and Czechia (violet) would be the ones to benefit most. This is probably because in Western Member States, middle-income groups devote a higher share of their expenditure to private transport than the poorest households. Hence, reducing excise duties would not reach the most vulnerable groups - it goes against the idea of a just transition.

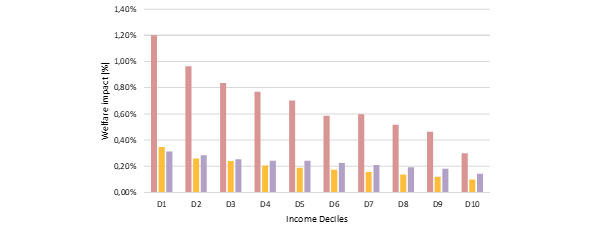

What if Member States make lump-sum transfers to the 50% poorest households, instead of reducing excise duties for everybody?

Welfare impact (% of total expenditure) in Policy Scenario 3

Source: García-Muros et al (2023)

The poorest households would have experienced a marked increase in their disposable income, confirming that targeted direct transfers are more effective than generalised measures, as stated also by the IMF and ECB.

Clearly, the crisis caused a regressive distributional impact. Following the results of IEEP and BC3 analysis, in the future, policymakers should account for national particularities and socio-demographic characteristics; governments should prioritise controls on electricity prices rather than fuel prices. Also, targeted measures to vulnerable groups will be more effective than broad support measures like tax reductions on energy commodities, since the latter would in fact benefit numerous groups in society who are less in need of support.

This article is based on the following report: García-Muros, Xaquín, Claudia Dias Soares, Jesus Urios and Eva Alonso-Epelde (2023) ‘Who took the burden of the energy crisis? A distributional analysis of energy prices shocks’, Policy Report, Institute for European Environmental Policy.