We are social beings, so it will come as no surprise that people’s relationships with other people have an impact on their ability to cope with energy poverty. In our recent study, we found that people use a range of different relationships (friends, family, advice agencies and others) to help them to access energy services (heat, mobility, and adequate electricity). In addition, having access to energy services can result in people being able to form or keep relationships: there are virtuous and vicious circles here. This means that when people do not have strong connections to others, or the ability to form such relationships, they are more vulnerable to the challenges of energy poverty.

Our research is based on qualitative interviews with people about their daily lives: we are using these to find out in detail how it feels to live with energy poverty in the UK, and how people’s relationships with each other impact on their ability to cope with energy poverty and vice versa. We are actually drawing on qualitative data collected in the past which aimed to understand people’s lived experience of energy poverty, and reusing it to answer new research questions about how people’s relationships with each other affect this experience. In this study we chose 12 interviews from a collection of 197 interviews conducted between 2004-2018: choosing cases where people reported either very good connections to other people, or isolation from other people. We analysed these interviews in detail to get a sense of what impact people’s relationships had on their experience.

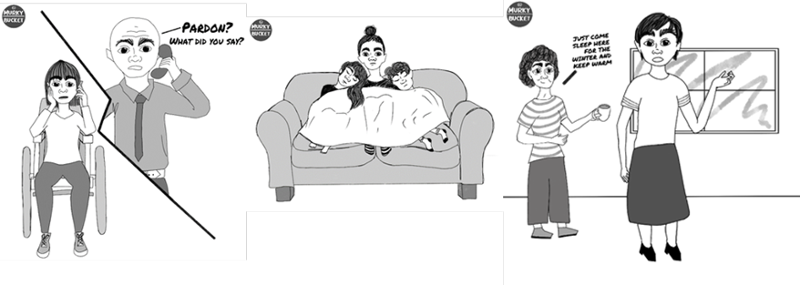

Our study showed that relationships, including those with friends, family, energy professionals and unknown others, can have a substantial impact on people’s ability to cope, and are often used to access resources, to share energy services and to find out about other forms of help. Relationships in the home are often affected by people’s energy poverty, so for instance a family might need to use their home differently in the winter because of the cold (see the ‘intimate’ picture, where a family has to spend more time in the same room to keep warm). People have to negotiate good relationships with agencies and services (e.g. energy companies, landlords and creditors), and depending on their background and resources this can be a challenge. In the ‘exclusion’ picture, we see an immigrant to the UK feeling like she may not deserve the help because of the way in which the government agency speaks to her on the phone. Even other people experiencing energy poverty are often unsympathetic about the situation, and it can be challenging to maintain dignity in the face of poverty stigma. In the ‘solidarity’ picture we see that, on the other hand, people can go to great lengths to help their neighbours.

Exclusion, intimate and solidarity pictures

Source: Mary Tallontire @murkybucket

So what happens when people are not able to make and maintain connections with others? Take one of our case studies: Marie is an older person, with health problems, and living alone in her detached bungalow. She has a daughter locally. She spends most of her time at home and her social life has been reduced to visits from family members, mainly her grown up daughter. Marie’s daughter is a big support: Marie’s ability to access to energy services depends heavily on her daughter acting as an intermediary, whether to organise renovations or to communicate with (and indeed pay) the energy supplier. In the winter, Marie has to choose between spending money on energy for heat, and using the phone, which further isolates her in her home. The fact that Marie lives alone, is in ill-health, is an older person, and recently bereaved make it challenging for her to access new support, and having only one person to ask for help (her daughter) makes her more vulnerable to experiencing the ill effects of energy poverty. You can see that isolation is likely to make accessing adequate energy services more challenging for Marie, and that having adequate heat directly affects her ability to maintain her relationship with her daughter.

Our study shows that people’s relationships with each other are an important topic to consider in energy poverty research, policy and practice. We see multiple instances of people being made more vulnerable if they do not have a strong social network to call on, and vice versa. People can cope much better if they have a supportive social network, and have the confidence to argue their case with the agencies they need help from (e.g. government, landlords, energy companies). Our work suggests that attempts to address energy poverty need to take into account the quality of people’s social relations, as well as the potential impact of policy and practice on social relations. In other words - combatting loneliness and isolation should be a part of combatting energy policy.

You can read the full paper about this research (in English) here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629618310004